A new study that sheds light on the extraordinary sensitivity of freshwater ecosystems and the long-term negative consequences of human impacts on biodiversity has been published in the most prestigious scientific journal, Nature. The research is based on a comprehensive dataset of 1,816 time series of freshwater invertebrate communities between 1968 and 2020 from 22 European countries, comprising 714,698 individuals of 2,648 taxa from 26,668 samples. Two Hungarian researchers, Dr. Gábor Várbíró from the Institute of Aquatic Ecology of the ELKH Centre for Ecological Research (CER), and Dr. Zoltán Csabai from the University of Pécs (PTE) also took part in the compilation and analysis of the data. Due to the persistent and newly emerging threats posed by climate change, invasive species, and new pollutants, the study calls for an immediate and intensified focus on mitigation strategies to rejuvenate the recovery of freshwater biodiversity.

Freshwater ecosystems hold significant significance in the context of global biodiversity. These water bodies provide habitat for numerous plant and animal species, and they play a crucial role in maintaining food chains and preserving ecological balance. Mitigation measures including wastewater treatment and hydromorphological restoration have historically shown promise in improving environmental quality and supporting the recovery of freshwater biodiversity.

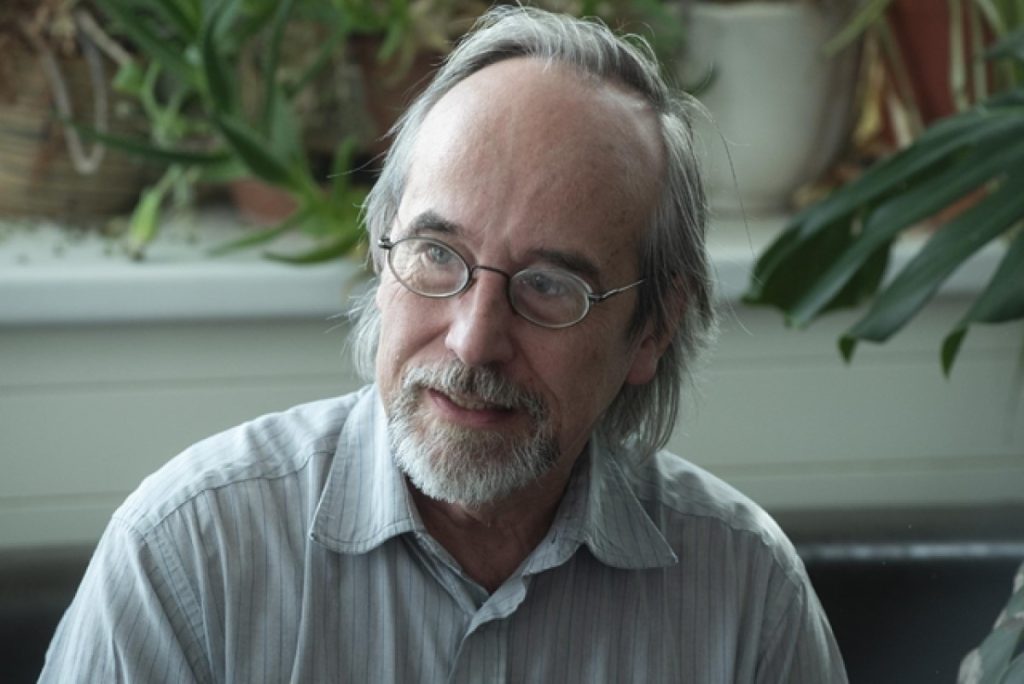

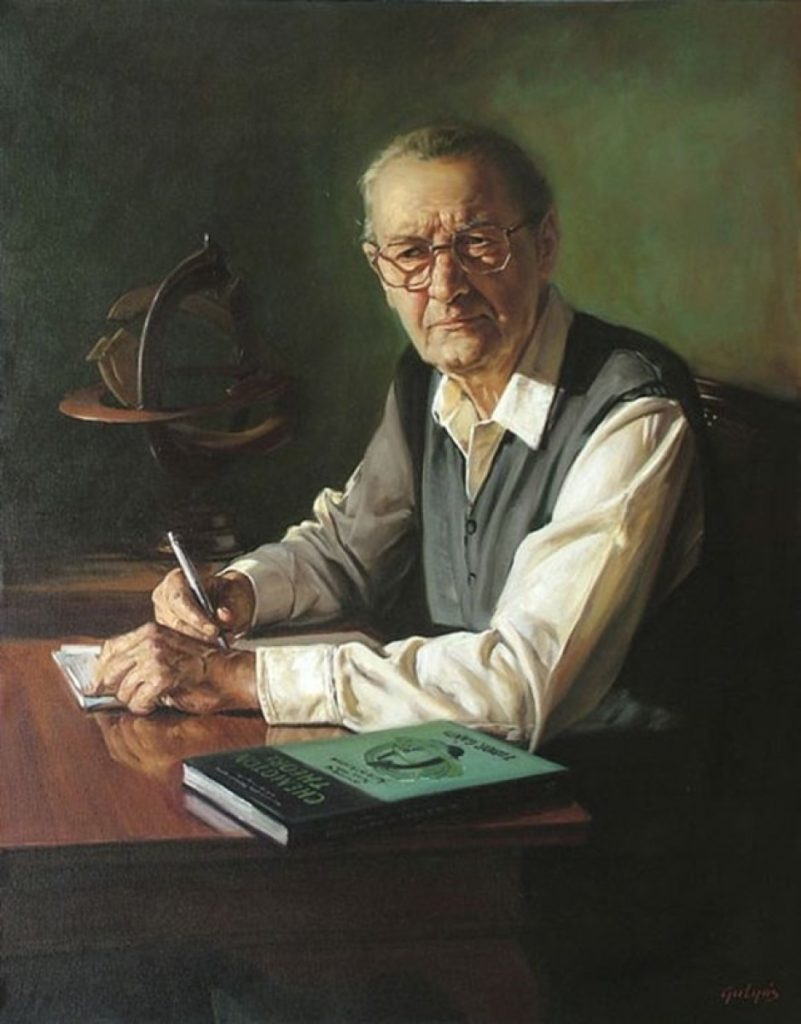

Together with a large international team the study’s first author, Prof. Dr. Peter Haase of the Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum in Frankfurt and Dr. Ellen A. R. Welti of the Smithsonian’s Conservation Ecology Center in the US analysed a comprehensive dataset of 1,816 time series of freshwater invertebrate communities between 1968 and 2020 from 22 European countries, comprising 714,698 individuals of 2,648 taxa from 26,668 samples. The analysis reveals a plateauing trend in the gains achieved.

The study indicates notable increases in taxon richness (0.73% per year), functional richness (2.4% per year), and abundance (1.17% per year) of freshwater organisms. These positive trends were prominent up until the 2010s, after which the recovery rates have significantly slowed down. Alarming patterns emerged in communities located downstream of dams, urban areas, and croplands, where the prospects for recovery appear grim. Moreover, sites experiencing higher rates of warming demonstrated fewer biodiversity gains, underlining the impact of climate change on freshwater ecosystems.

The study underscores the vulnerability of inland waters to a range of anthropogenic pressures, including pollution, urbanization, and the impacts of climate change. Despite past regulatory efforts, including landmark legislations like the ‘US Clean Water Act’ of 1972 and the EU Water Framework Directive of 2000, the researchers emphasize that more needs to be done to counteract the increasing stressors that threaten these vital ecosystems.

The researchers suggest that while the gains witnessed in the 1990s and 2000s could be attributed to successful water-quality enhancements and restoration endeavours, the observed deceleration in the 2010s suggests a diminishing effectiveness of the current measures. These measures led to a significant reduction in organic pollution and acidification, beginning around 1980. Over the past 50 years, these steps have contributed to the containment of wastewater pollution and resulted in improvements in freshwater biodiversity. Unfortunately, as the number and impact of stressors continue to increase worldwide, the improvements resulting from past legislation are lessening and freshwater systems remain degraded in many places. With the persistent and emerging threats posed by climate change, invasive species, and new pollutants, the study calls for an immediate and intensified focus on mitigation strategies to rejuvenate the recovery of freshwater biodiversity.

The involvement of two Hungarian scientists. Dr. Gábor Várbíró from CER and Dr. Zoltán Csabai from PTE adds a significant layer of expertise to this critical research effort. Their collaboration within the international team has shed light on the status of European freshwater biodiversity and underscored the urgent need for actionable conservation measures.

Dr. Gábor Várbíró said, “Our findings raise a critical alarm for the health of European freshwater ecosystems. The slowdown in recovery rates demands a comprehensive re-evaluation of existing mitigation measures and the implementation of new, adaptive strategies. Time is of the essence, and we must act swiftly to protect these essential ecosystems.”

The study underscores the necessity of a multi-faceted approach, engaging policymakers, scientists, and communities at large, to ensure the long-term vitality of freshwater ecosystems. As Europe and the world face increasingly complex environmental challenges, collaborative and immediate actions are crucial to reverse the trend of stagnating freshwater biodiversity recovery.

Photos: Gabriella Bodnár, – Centre for Ecological Research