Climate change cannot be fixed by simple measures such as planting trees. New research published in Nature Geoscience journal shows that restoring our natural terrestrial habitats can remove much smaller amount of the carbon from the air than previous models suggested. Focus needs to be on rapidly reducing emissions and ensuring that initiatives are equitable and focused on climate change adaptation.

Senior author Ákos Bede-Fazekas, research fellow at the HUN-REN Centre for Ecological Research outlines that policymakers should take a holistic approach when considering ecosystem restoration, with a focus on biodiversity and nature’s contribution to people, while reducing emphasis on carbon sequestration. In the last 10 years, habitat restoration has been increasingly used as a means for climate change mitigation, a key element in response to both the climate crisis and the biodiversity emergency. The recurring theme being that it could offset a substantial fraction of human carbon emissions. This view was supported by earlier modeling results – but these followed the principle of “plant trees everywhere possible!”. Ecosystem restoration is a more complex process that requires greater consideration than simply establishing seminatural forests or, worse, creating tree plantations.

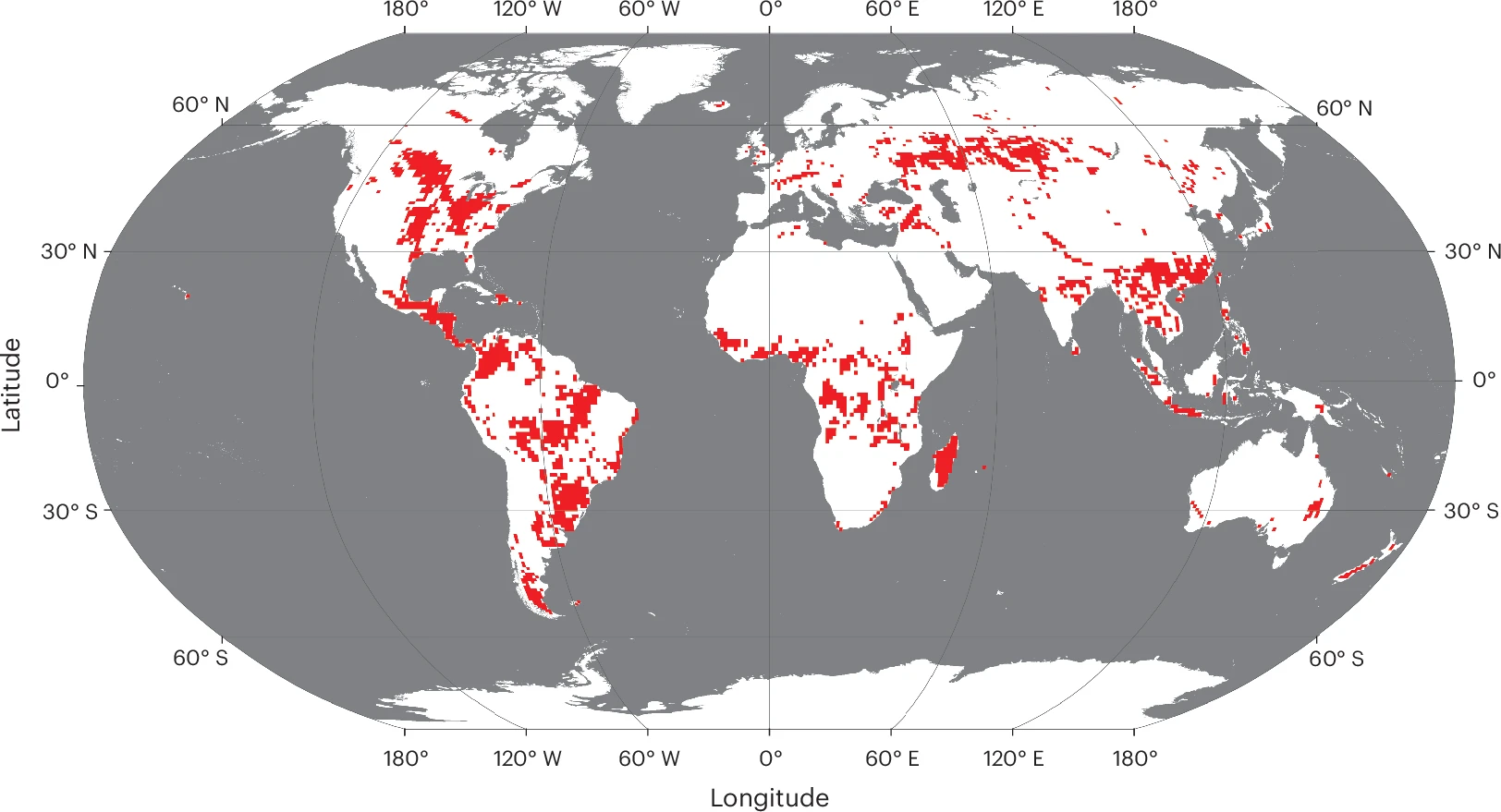

The international group of scientists was led by Csaba Tölgyesi, of University of Szeged, who highlighted: “Carbon sequestration modeling necessitates a more inclusive approach, considering all possible natural ecosystem types. Forests will store carbon mostly in their biomass, grassland in the soil. All ecosystems are good where they belong.”

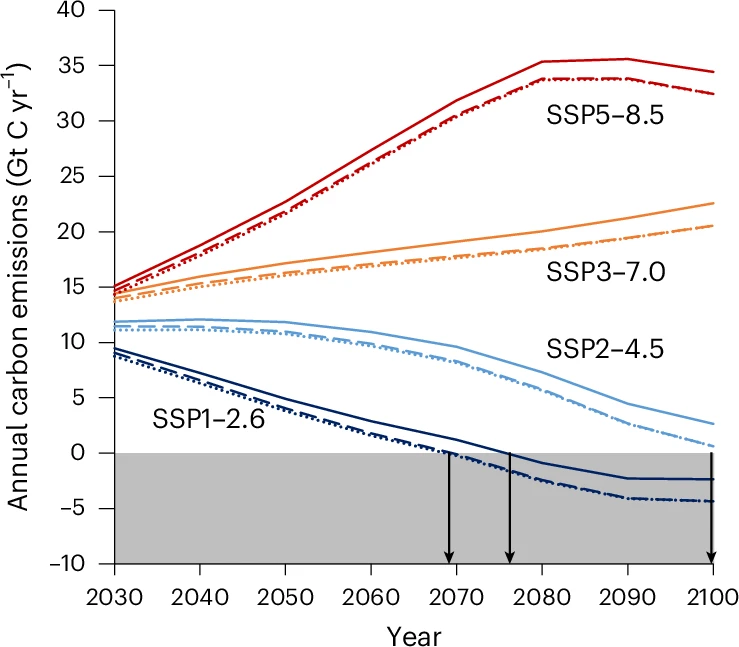

The available models and predictions still had some problematic assumptions and incorrect input data, which the researchers wanted to rectify to have a clearer view of the potential of ecosystem restoration in climate change mitigation. Hence, they made a model much more realistic than the previous ones had been. For example, their model does not force restoring forests in every location they are predicted to be suitable – including established grasslands with high carbon sequestration potential or productive agricultural lands. This led them not to a slight adjustment, but to a massive difference from previous carbon capture potentials. The scientists found that ecosystem restoration has a measurable but limited effect on atmospheric carbon concentrations if compared to previous predictions. In the greenest of all climate scenario, 17 percent of human emissions can be recaptured by 2100, while in the business-as-usual (most pessimistic) scenario, it is less than four per cent.

These model forecasts of climate change mitigation via ecosystem restorations suggest an urgent need for a change of direction in polices to transition to a low carbon economy.

Fellow author, Caroline Lehmann, of Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh added: “With the limited likelihood of significantly mitigating climate change through global ecosystem restoration in the short or medium term, policies need to prioritize restoration activities in favor of vulnerable communities and biodiversity to support the resilience of nature and people with ongoing climate change.”

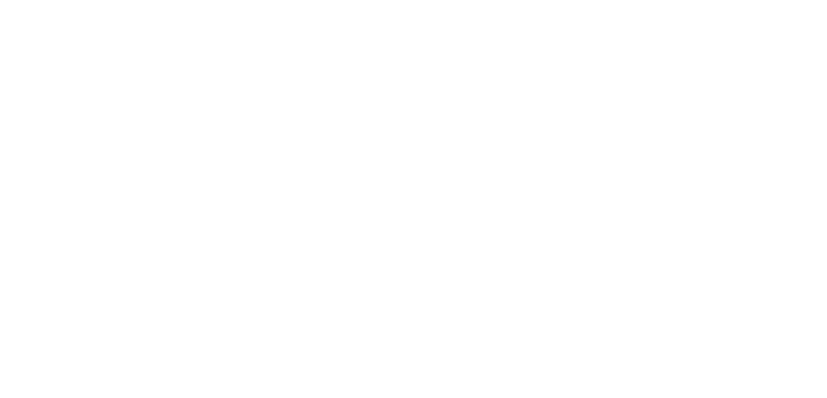

Historically, the burden for ecological restoration has been placed on the Global South with the offsetting and carbon sequestration agenda driven by the Global North. Not only is it unjust that the communities who did not create the problem of climate change bear the brunt of its solution, the study shows that a large number of potential priority regions for restoration for carbon gain are located across the Global North.