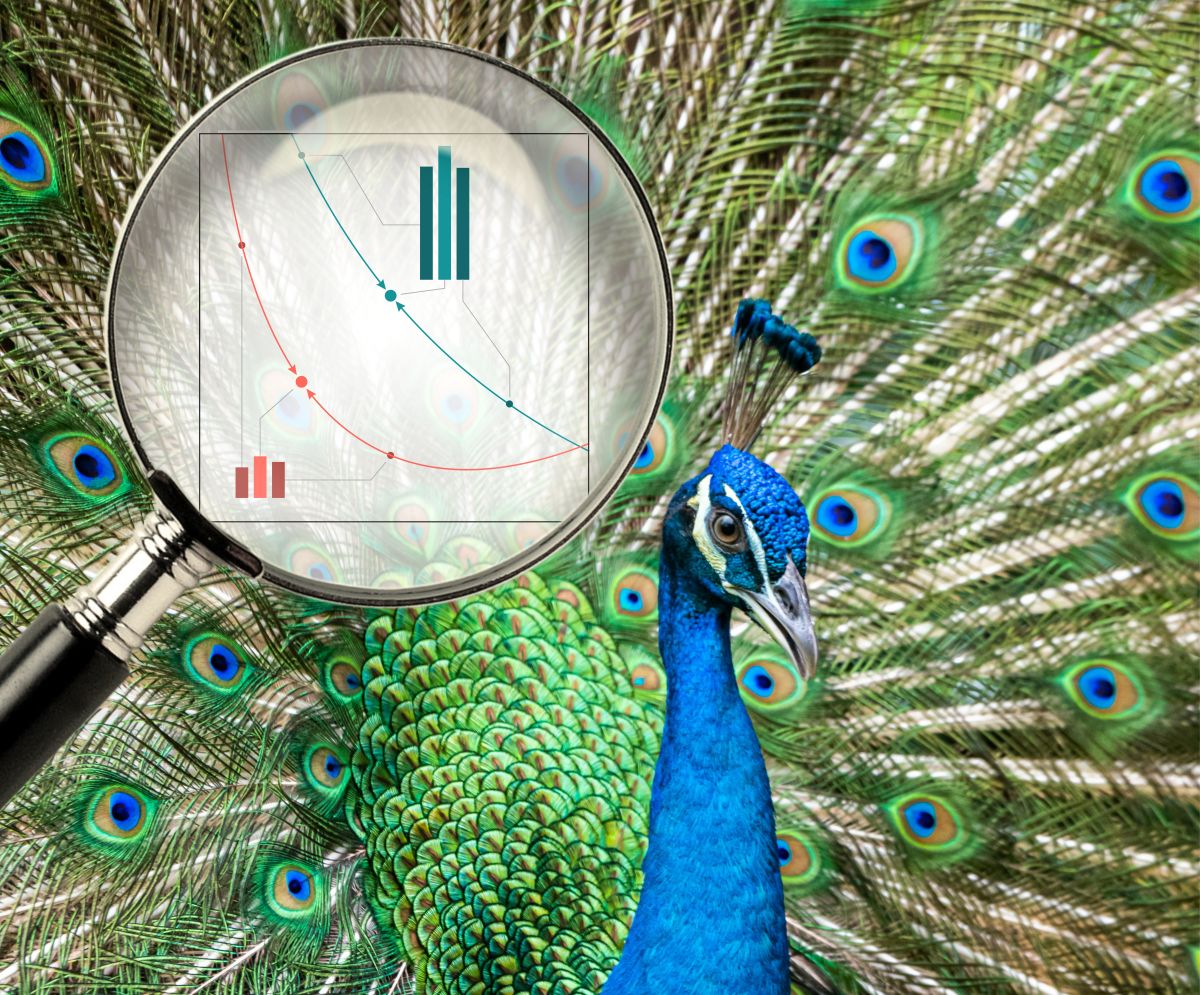

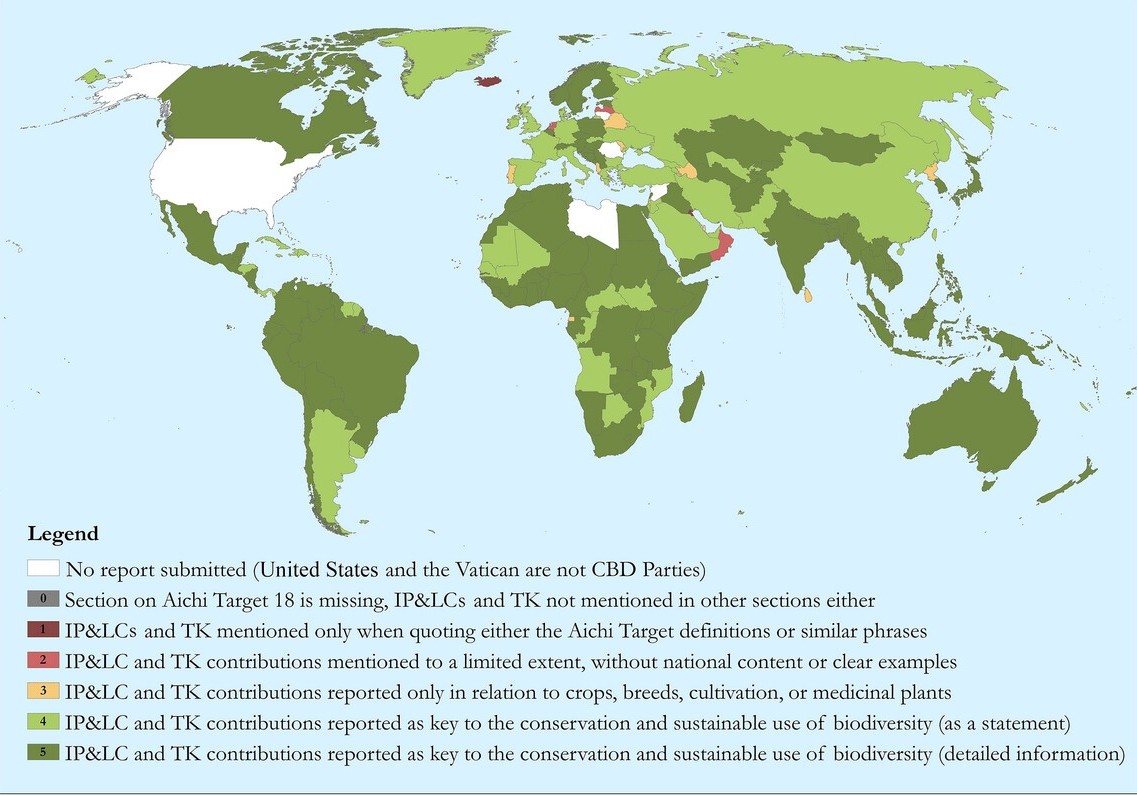

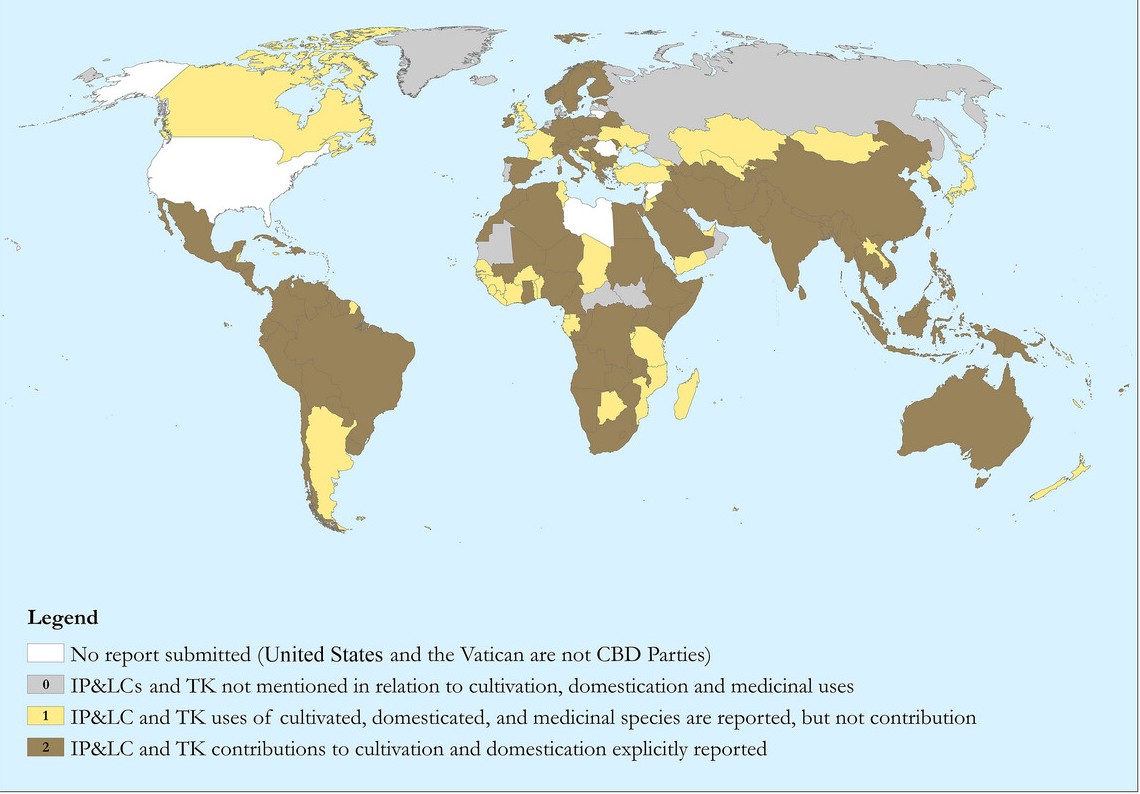

Solitary wild bees and wasps play a key role in ecosystem functioning – both as pollinators and as biological pest control agents. Yet we still know surprisingly little about the life history, population dynamics and ecological interactions of many species. Researchers at the HUN-REN Centre for Ecological Research have recently published a study presenting the first detailed, step-by-step protocol for using trap nests to study cavity-nesting Hymenoptera, i.e., solitary bees and wasps (Fig. 1). Standardising this sampling method will allow data collected in different parts of the world to become comparable, which is an important step towards improving pollinator conservation.

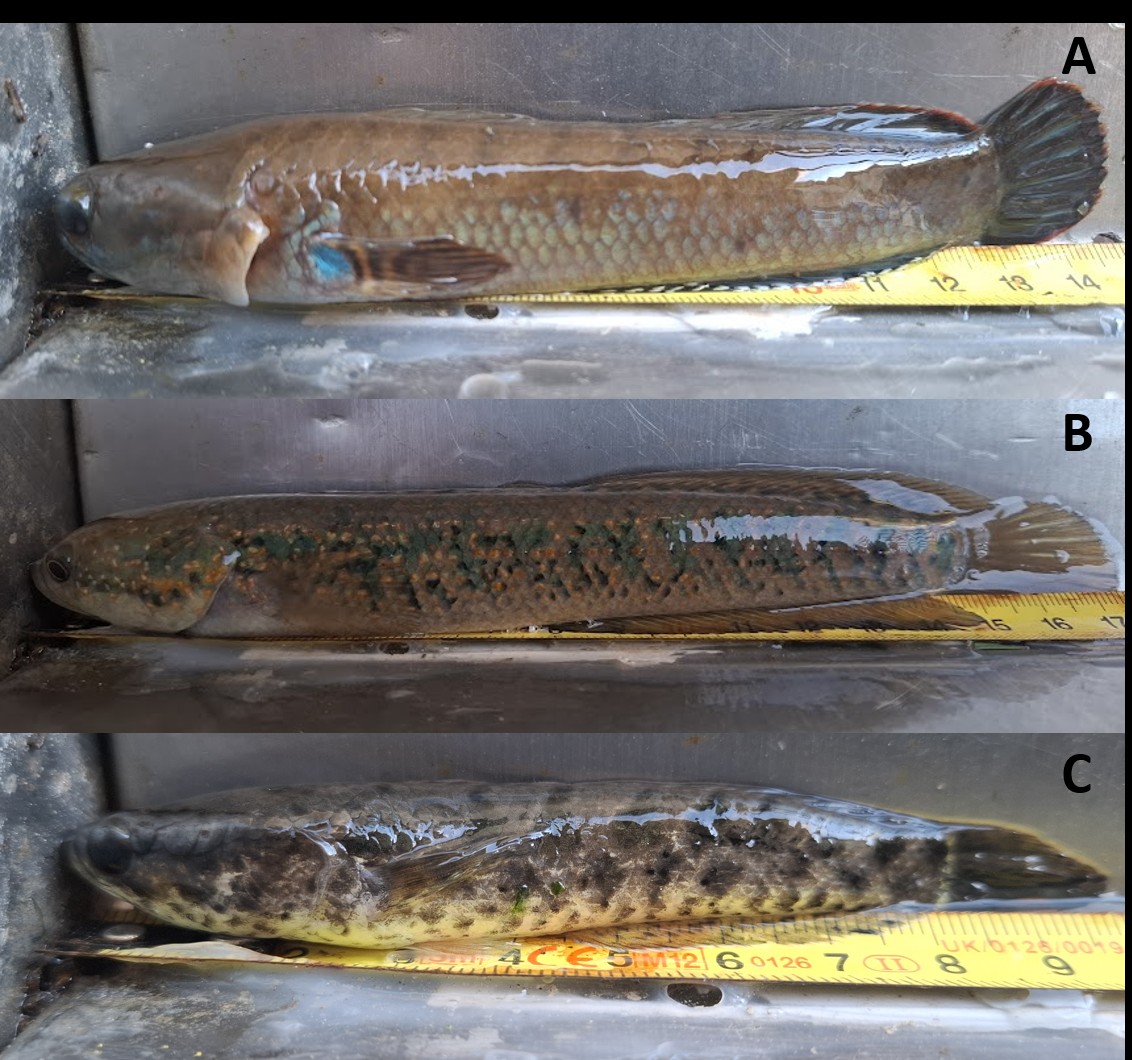

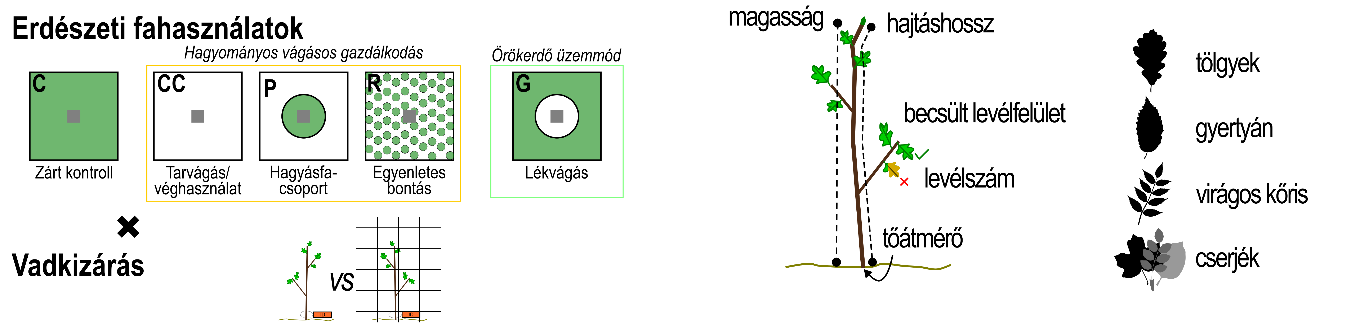

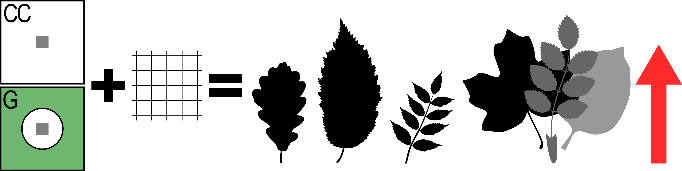

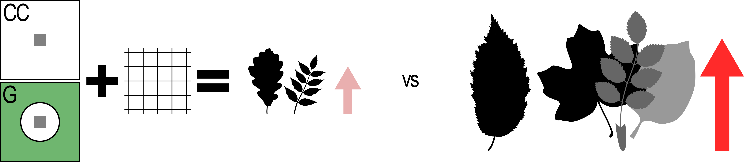

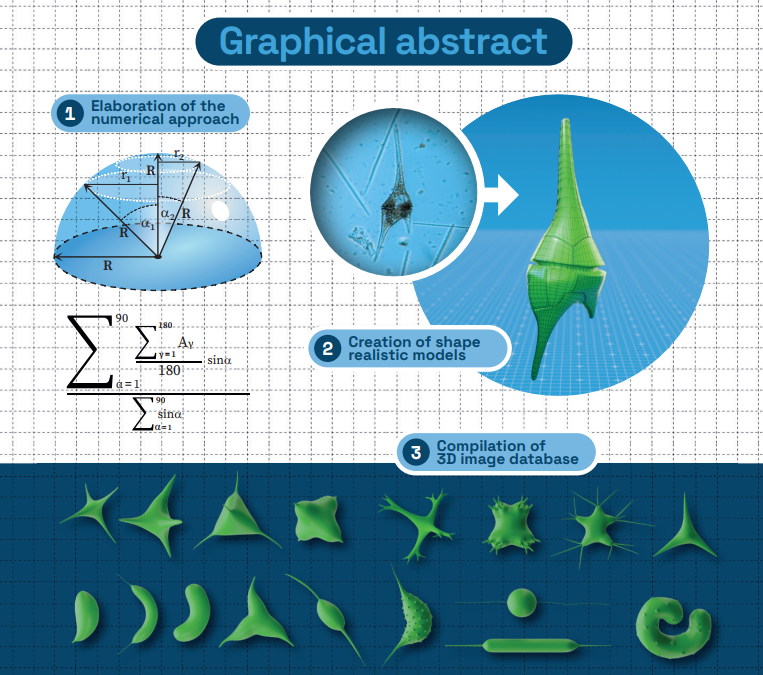

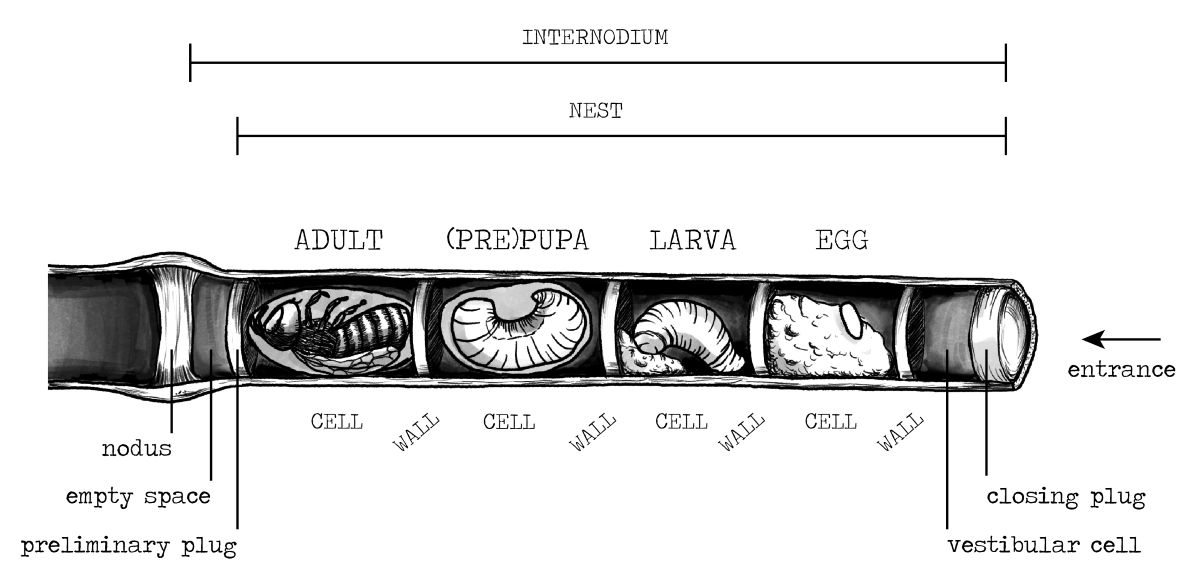

The trap nests used by researchers may look familiar to many people: “bee hotels”, increasingly common in gardens, consist of hollow stems or wooden blocks with drilled holes (Fig. 2 – Main foto). These structures mimic natural nesting sites and attract cavity-nesting bees and wasps. Inside the cavities, brood cells are constructed where bee and wasp larvae develop on the food provisions stored by the mother (Fig. 3). The special advantage of this method is that it allows researchers not only to identify the species present but also to study a range of ecological processes – including nesting behaviour, the presence of parasites, and the use of environmental resources such as food and nesting materials.

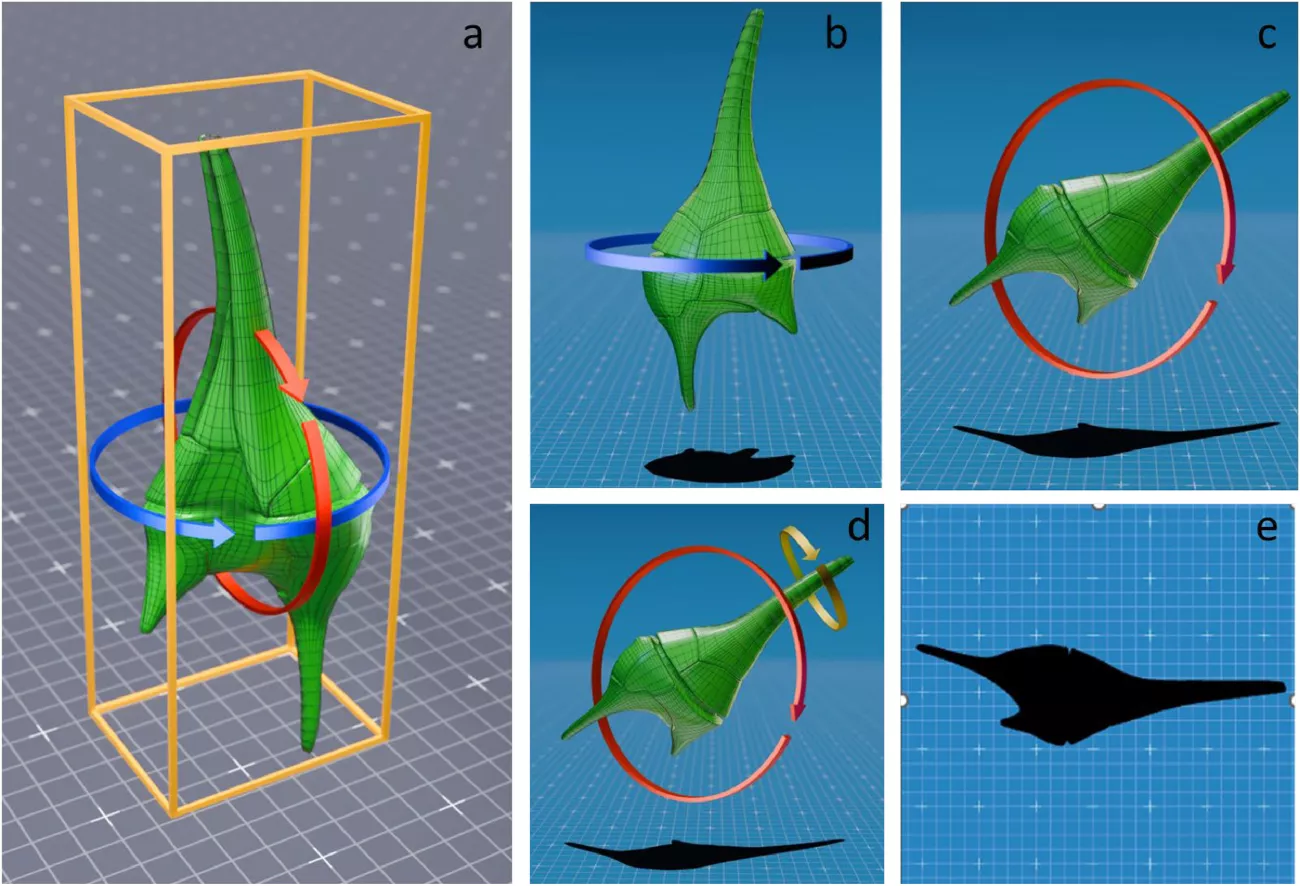

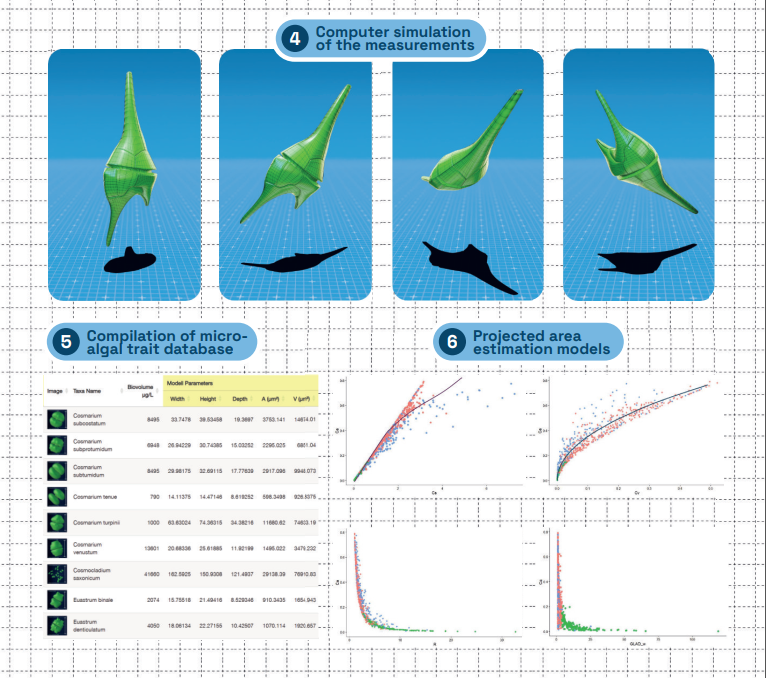

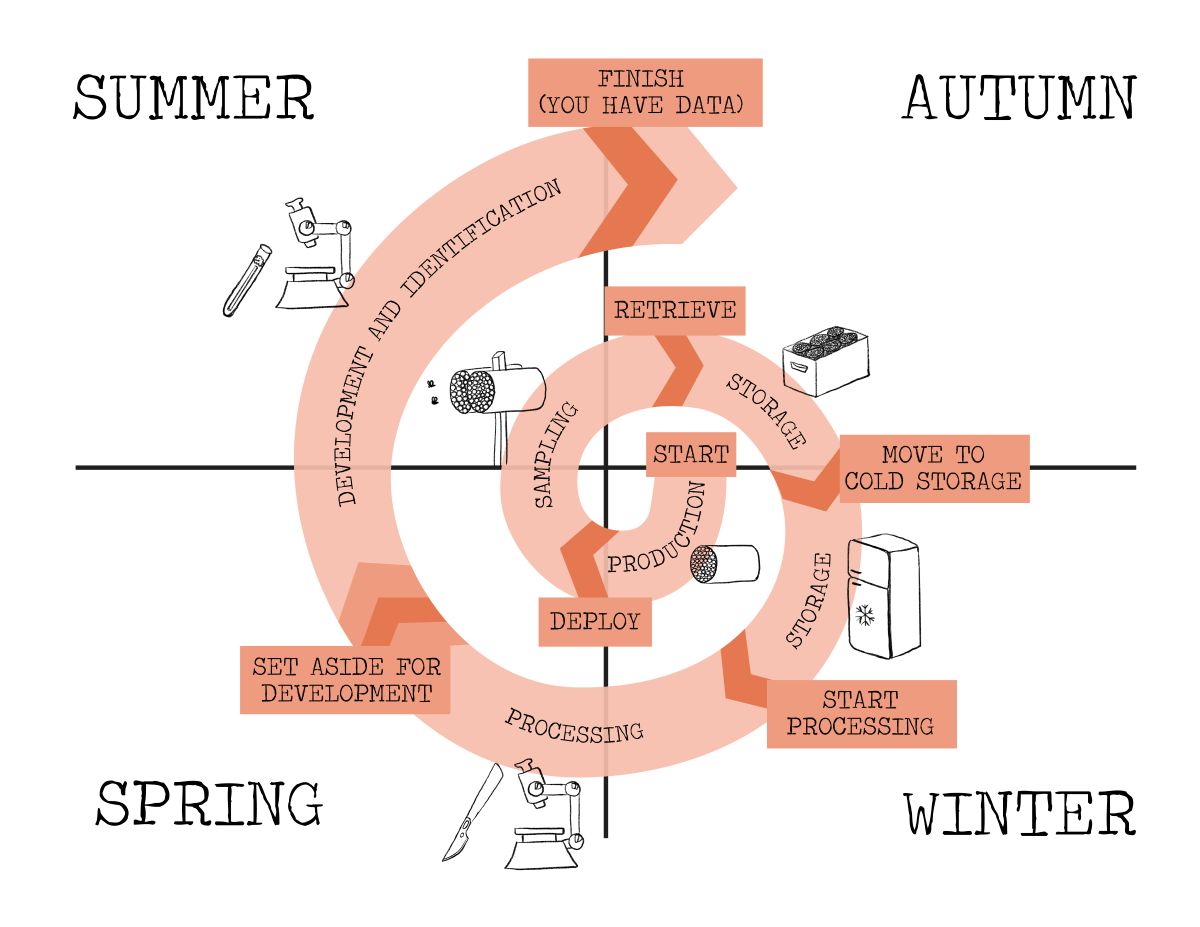

The newly published study provides detailed guidance on how to construct trap nests, when and how to place them in the field, and how to collect and process the samples found within them. The entire process can take up to nearly two years – from deploying the nests, through larval development and overwintering, to the final identification of species (Fig. 4).

“Trap nests contain a remarkable amount of ecological information. From a single nest we can learn what food the nesting individuals collected, what materials it used to build the nest, and which natural enemies harnessed the offspring,” said Áron Bihaly, the first author of the study. “The aim of the protocol is to ensure that researchers around the world collect these data using the same methods, making the results of different studies comparable.” He added that “although the data collection process can be lengthy, it allows us to obtain detailed information that is almost impossible to collect with any other sampling method.”

One advantage of the method is that it can provide valuable data with relatively little fieldwork. The nests are placed in the field in spring and collected in autumn, meaning that the samples provide insights into ecological processes throughout an entire season. The analysis of nests reveals not only which species are present, but also information about the structure of local insect communities, their reproductive success and how they use resources available in the surrounding landscape.

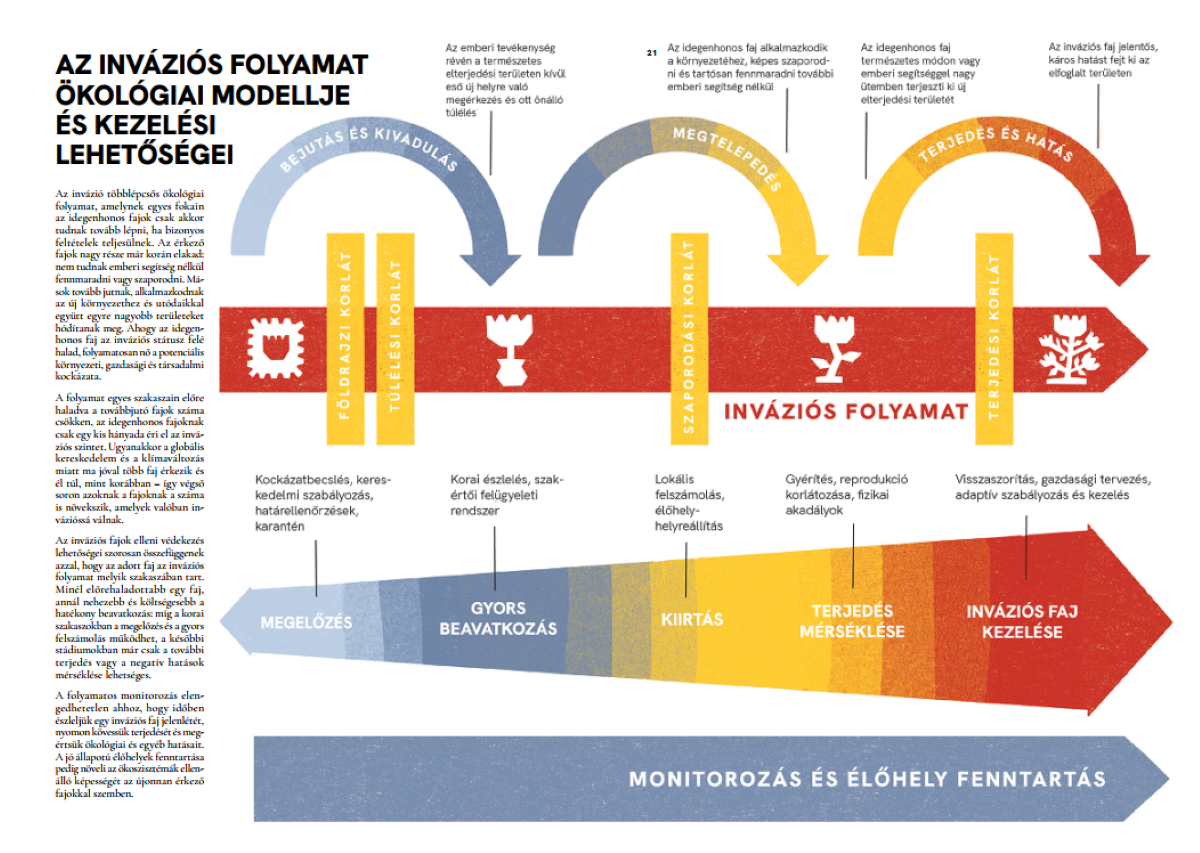

The researchers emphasise that standardised methods are particularly important in the context of the global pollinator crisis. Wild bees and other hymenopteran insects provide many ecosystem services, including pollination and the natural control of pest species. Monitoring changes in their populations is therefore essential for designing effective conservation measures. Trap-nest sampling has proven to be a particularly useful tool in this effort.

One of the online supplementary materials of the publication provides a detailed, illustrated guide to the bee and wasp species that nest in cavities in Hungary. This guide can also be useful for members of the public who maintain bee hotels. “Such protocols are not only useful for mainstream research, but they also open the door to involving wider communities in observations,” said Edina Török, one of the lead authors of the study. “For example, we are launching a survey of wild bees in Budapest with the involvement of local residents as part of the citizen-science UrbanBEE project. Within the project, we distributed bee hotels to participants, who record a few basic observations. Initiatives like this help us better understand how pollinators live in urban environments.”

The researchers hope that the new protocol will contribute to the wider and more consistent use of trap nests, which in the long term may support the conservation of pollinators and other insects, strengthen international ecological research collaborations, and help design more precise agri-environmental measures and habitat restoration efforts.

Related publication:

Bihaly Áron Domonkos et al. (2026): A standardised protocol for sampling cavity-nesting Hymenoptera using trap nests. Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

https://doi.org/10.3897/jhr.99.183051